CALL FOR PAPERS: MULTILINGA

Special Issue: Learning, re-learning, and un-learning Language(s) in the home during Covid-19.

Guest Editors: Fatma Said & Kristin Vold Lexander

Zayed University, UAE & Inland Norway University of Applied Sciences

Fatma.said@zu.ac.ae & kristin.lexander@inn.no

Epilogue: Dr. Lyn Wright

The University of Memphis, USA

The continuing global COVID-19 pandemic changed the way in which education has traditionally taken place with a ‘shift away from learning and teaching in traditional settings with physical interactions’ (UNESCO, 2020a, p. 7), towards a distance, online or blended approach. In many cases combining a learning from home model with support from teachers and schools (Said et al, 2021). Formal learning, and with it the education system, has entered the home in a way that it has never done so previously. In this context, ‘the family more than ever constitutes a learning space, in which parents and caregivers act as primary guides to support their children’s learning at home’ (UNESCO, 2020b, p. 1). Unquestionably this ‘learning’ has gone beyond that of school subjects and given the intense space and time sharing that families have experienced, there is no doubt that the learning, re-learning and un-learning of multiple languages has also taken place at home among multilingual families. The family has always been a learning space and recognized as such in anthropology, language socialization studies and most prominently in family language policy studies (Schalley et al, 2020; Lanza & Lexander, 2019; Said & Hua, 2019; Gomes, 2018; Curdt-Christiansen & Lanza, 2018; Piller & Gerber, 2018; Fogle, 2012; 2013; King & Fogle, 2017; Okita, 2002). In the context of lockdowns or hybrid learning, everyday subtle qualities of the home environment, socio-affective factors of language learning and language socialization (Ochs & Schieffelin, 1984) become more pronounced.

This special issue therefore seeks to present a set of empirical papers that describe and chronicle the central role the family unit has played in the learning and use of multiple languages during the super-charged intense tempo-spatial home environment created by the pandemic restrictions. Families spent the most time together and this resulted in increased interaction and more joint activities than before the pandemic. Some excellent research has already taken place with findings emerging in short papers or media reports. These few studies have so far illustrated how the lockdown at home has offered (mostly) favourable conditions for the learning of home or heritage languages (HL) (Li Sheng et al, 2021; Afreen & Norton 2021; Escobar, 2020; Hardach, 2020). There is, however, a lack of research on how the lockdown may interfere with the dynamics of language shift or what the effects of languages of instructions entering the home in unprecedented ways may have had on HL learning. Families that did not speak the language of instruction in their homes for example were forced to speak it with their children in order to facilitate learning (see Chik & Benson, 2021 for a commentary). The volume seeks to explore the realities of private language planning, learning, and use within the home during this unique period of existence; and from that perspective, we ask the following questions:

- How have the lockdown (and pandemic) conditions shaped family language policies?

- How has the influx of English/ any other language into the home as a result of LMI (Language of medium of instruction) shaped the family’s use and learning of their home language(s)/heritage language(s)?

- How have the pandemic conditions affected the home language learning and literacy learning environments?

- What is the relationship between families’ (internal) language policies and those of the school’s (external)? How has this relationship affected the internal home language policies?

- What roles have different family members taken on in the process of learning and re-learning languages during lockdown? In particular, what did we learn about the nature of child agency and language learning during the lockdown?

- How has fatigue in attending to educational and other needs of children affected heritage or home language(s) learning efforts?

- For families with access to technology, how has constant and easy access to digital content augmented the learning of language(s) in the home during the lockdown?

Papers are invited to answer one or more of the questions above or those related to the special issue’s theme with regards to the learning, re-learning and un-learning of languages within the home and among family members. We are interested in mixed methods approaches to data collection as well as descriptions of digital ethnography, other virtual methodologies, and creative data collection methods are particularly welcome. We are also eager to receive papers from different (and usually underreported) geographical and socio-economic contexts as well as varied and diverse family constellations.

Submission guidelines

Interested researchers should submit a 500-word proposal (with references) and a short 100-word author biography by 31st January 2022. Submission of contributions should be written in English. Email submission is preferred and should be directed to the special issue editors at this email address: Fatma.Said@zu.ac.ae . Notifications of acceptance will be sent out by the 1st March 2022.

Once accepted, full papers of no more than of 7,000 words, including all elements (title page, abstract, notes, references, tables, biographical statement, etc.) are due on 1st June 2022. The style guideline of Multilingua should be followed: https://www.degruyter.com/journal/key/MULT/html.

References

Afreen, A., & Norton, B. (2021). COVID-19 and heritage language learning. https://rscsrc.ca/sites/default/files/Publication%20%2367%20-%20EN%20-COVID19%20and%20Heritage%20Language%20Learning_0.pdf

Chik, A &., Benson, P. (2021). Commentary: Digital language and learning in the time of coronavirus. Linguistics and Education, Volume 62.

Curdt-Christiansen, X.L. &., E. Lanza. (2018). Language management in multilingual families: Efforts, measures and challenges. Multilingua 37 (2): 123-130.

Escobar, A. (2020). From Tagalog to Korean, these Asian American families are using quarantine to learn their families’ languages. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/asianamerica/tagalog-korean-these asian-americans-are-using-quarantine-learn-theirn1239013

Hardach, S. (2020). In Quarantine children pick up parents’ mother tongues. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/10/parenting/family-second-language-coronavirus.html

Fogle, L.W. (2012). Second language socialization and learner agency: Adoptive family talk. Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Fogle, L. W. (2013). Parental ethnotheories and family language policy in transnational adoptive families. Lang Policy 12: 83–102

Gomes, R. L. (2018). Family Language Policy Ten Years on: A Critical Approach to

Family Multilingualism. Multilingual Margins 5(2): 50–71.

King. K. A. &., L.W. Fogle. (2017). Family Language Policy. In Language Policy and Political Issues in Education. Encyclopedia of Language and Education edited by Teresa McCarty and Stephen May, 315 327. New York: Springer.

Lanza, E., & Lexander, K. V. (2019). Family Language Practices in Multilingual Transcultural Families. In Montanari, S., & Quay, S. (eds.) Multidisciplinary Perspectives on Multilingualism (pp. 229-252). De Gruyter Mouton.

Ochs, E., & Schieffelin, B. (1984). Language acquisition and socialization. Culture theory: Essays on mind, self, and emotion, 276-320.

Okita, T. (2002). “Invisible work: Bilingualism, language choice and childrearing in international families.” Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Piller, I. &., L. Gerber. (2018). Bilingual advantage and the monolingual mindset. International Journal of Bilingualism and bilingual education 25 (4), 424-438.

Rubino, A. (2014). “Trilingual talk in Sicilian-Australian migrant families: Playing out identities through language alternation”. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Said, F.; Jaafarawi, N., & Dillon, A. (2021). Mothers’ accounts of attending to educational and everyday needs of their children at home during COVID-19: The case of the UAE. Social Sciences special Issue on Family, Work and Welfare: A gender lens on COVID-19. Soc.Sci. 2021, 10, 141 https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10040141

Said, F., & Zhu, H. (2019). “No, no Maama! Say ‘Shaatir ya Ouledee Shaatir’!” Children’s agency in language use and socialisation. International Journal of Bilingualism, 23(3), 771-785.

Schalley, Andrea C; Eisenchlas, Susana A. (2020). Handbook of Home Language Maintenance and Development, De Gruyter Mouton

Sheng, L., Wang, D., Walsh, C., Heisler, L., Li, X., & Su, P. L. (2021). The bilingual home language boost through the lens of the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 3012.

UNESCO (2020a). Education in a post-COVID world: Nine ideas for public action. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000373717.

UNESCO (2020b). UNESCO COVID-19 Education Response – Education Sector issue notes no.23 April 2020 https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000373512.

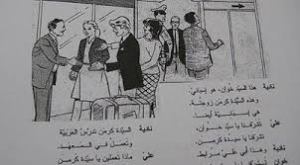

Of course the reactions to such a video are, “you see, oh my God! Arabic is dying”, or “Goodbye the Arabic language”, or “you see and they tell us it is not dying”, or “we’ve lost that’s it” and “look at these kids, they even speak with an American accent but can’t name anything in Arabic” on and on. For this reason I have not supplied the video here because in these situations people feel that it’s okay to criticise the children, well it is not! It is not their fault they were recorded, how do we know if they gave their permission, how do we know their parents know this video is being shared online? (I don’t want to get into the ethics of sharing things without permission, that will need to be another post). But if they do not know these words in Arabic then we cannot demonise them for that, it’s not their fault.

Of course the reactions to such a video are, “you see, oh my God! Arabic is dying”, or “Goodbye the Arabic language”, or “you see and they tell us it is not dying”, or “we’ve lost that’s it” and “look at these kids, they even speak with an American accent but can’t name anything in Arabic” on and on. For this reason I have not supplied the video here because in these situations people feel that it’s okay to criticise the children, well it is not! It is not their fault they were recorded, how do we know if they gave their permission, how do we know their parents know this video is being shared online? (I don’t want to get into the ethics of sharing things without permission, that will need to be another post). But if they do not know these words in Arabic then we cannot demonise them for that, it’s not their fault. By no means am I playing down the seriousness of the fact that as children of their ages they should really know these common nouns. But what I am saying is that it is not as gloomy as we might think it is on the surface. In other words, if these children get a good grounding in Arabic over the next few years they will master it by the time they are teenagers. They will of course need the same level of good language teaching in English too since some countries (mainly outside Europe save the Far East) are introducing English earlier and earlier into the curriculum. The children therefore need to, and I have said this here on this blog before, master two languages- and do so well. It is not impossible and as long as both school and home provide the correct input the child will develop at the same pace as a monolingual child. But where the input is not correct (not being prescriptivist here but a certain standard of language is needed) the child will fail to master language and in some cases both languages. Countries such as Denmark and others prefer to introduce English to their children at the age of 9 (there is variation with some starting at 8 whilst others wait until 11). So there are a number of models when it comes to providing children access to more than one language at the state level (National Language Planning). Each is valid and each has a methodology which supports it to make it work for the children because they are after all the future of the country. So each country, community or education system must find a way that suits their students (and please none of that copy & paste business!) and enact it well offering support where needed.

By no means am I playing down the seriousness of the fact that as children of their ages they should really know these common nouns. But what I am saying is that it is not as gloomy as we might think it is on the surface. In other words, if these children get a good grounding in Arabic over the next few years they will master it by the time they are teenagers. They will of course need the same level of good language teaching in English too since some countries (mainly outside Europe save the Far East) are introducing English earlier and earlier into the curriculum. The children therefore need to, and I have said this here on this blog before, master two languages- and do so well. It is not impossible and as long as both school and home provide the correct input the child will develop at the same pace as a monolingual child. But where the input is not correct (not being prescriptivist here but a certain standard of language is needed) the child will fail to master language and in some cases both languages. Countries such as Denmark and others prefer to introduce English to their children at the age of 9 (there is variation with some starting at 8 whilst others wait until 11). So there are a number of models when it comes to providing children access to more than one language at the state level (National Language Planning). Each is valid and each has a methodology which supports it to make it work for the children because they are after all the future of the country. So each country, community or education system must find a way that suits their students (and please none of that copy & paste business!) and enact it well offering support where needed. efer to this as family language policy (see also the post before this one), where parents or a parent decide on the languages used within the home, outside the home and how they wish to support those. A great number of research is showing that the family is the centre of the well-being of the child and this also includes the child’s linguistic development. Parents (if they want their children to master Arabic) should be prepared to practically work towards it. It is not enough to buy DVDs or books, they must read to the child, listen to the CDs/DVDs (and explain to the child) and importantly talk to the child in Arabic (any form of Arabic).

efer to this as family language policy (see also the post before this one), where parents or a parent decide on the languages used within the home, outside the home and how they wish to support those. A great number of research is showing that the family is the centre of the well-being of the child and this also includes the child’s linguistic development. Parents (if they want their children to master Arabic) should be prepared to practically work towards it. It is not enough to buy DVDs or books, they must read to the child, listen to the CDs/DVDs (and explain to the child) and importantly talk to the child in Arabic (any form of Arabic).

o, but I always felt as if it was not enough. I felt that in addition to all of the above the material had to also challenge students to think deeply about the way they used language. Of course I do not mean 5 or 6 year olds but 8, 9, 10 and secondary school students (especially native speakers of Arabic) deserve material that challenges their thinking.

o, but I always felt as if it was not enough. I felt that in addition to all of the above the material had to also challenge students to think deeply about the way they used language. Of course I do not mean 5 or 6 year olds but 8, 9, 10 and secondary school students (especially native speakers of Arabic) deserve material that challenges their thinking.